Kurdish Youth: Similarities and Differences

Reha Ruhavioğlu

There are approximately 20 million young people between the ages of 15 and 29 in Türkiye. With a young population of nearly a quarter of the population, Türkiye is considered one of the youngest countries in the world and Europe. On the other hand, it is not easy to find official data on the Kurdish population in Türkiye, except for the 1927 census, which asked about ethnic and religious affiliation, and the 1965 census, which asked about mother tongue. According to both of these official data, the proportion of Kurds in Türkiye is around 7-9 percent.

Due to the circumstances of the period, the limited inclusiveness of the censuses and the traditional Kurdish policy of official institutions cast doubt on the reliability of these figures, while various independent projections estimate that the Kurdish population in Türkiye today is between 15 and 18 million. (As an example, 2020 Turkish Statistical Institute birth rate data using the model presented in Servet Mutlu’s 1990 article “Ethnic Kurds in Turkey: A Demographic Study”)

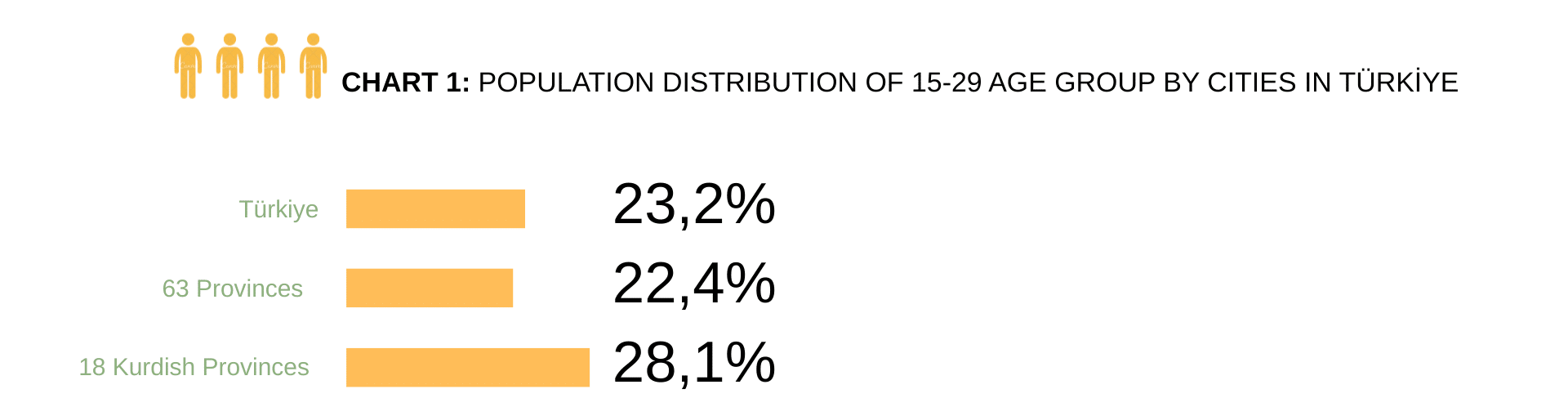

In Türkiye, one of the youngest countries in the world and in Europe, the proportion of young people aged 15–29 in the population is 23 percent. In the 18 cities with a high Kurdish population, the proportion of young people aged 15–29 is 28 percent, while in the rest of Türkiye’s cities this rate is 22.4 percent. If we also consider the provinces where Kurds have migrated heavily—such as Istanbul, İzmir, Ankara, and the Mediterranean provinces—we can estimate that the young Kurdish population in Türkiye is even higher.

Both the dynamics of the world and the fact that Kurds live densely outside their own geography, together with the increasing proportion of young Kurds and the unique differences in their experiences and life practices, make Kurdish youth a particularly intriguing group within the general category of “youth” in Türkiye. Fed by this curiosity, the report of a research project that has been ongoing for approximately one year was recently published under the title “Kurdish Youth ’20: Similarities, Differences, Changes” and shared with the public.

With the support of the British Embassy and the Heinrich Böll Stiftung Türkiye Representation, the report of the project conducted by Yaşama Dair Foundation, the Kurdish Studies Center, and Rawest Research simultaneously portrays the political and social preferences of Kurdish youth, outlining their concerns, expectations, future plans, and worldview, while also highlighting the similarities and differences between Kurdish youth and the broader youth population in Türkiye.

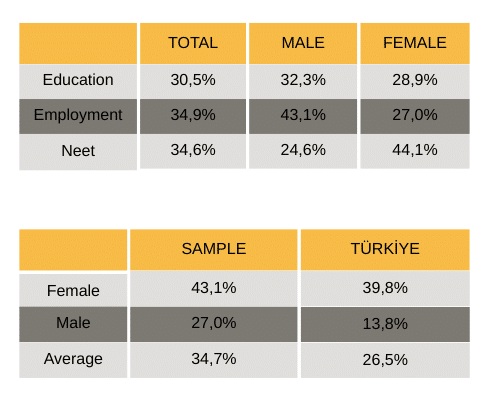

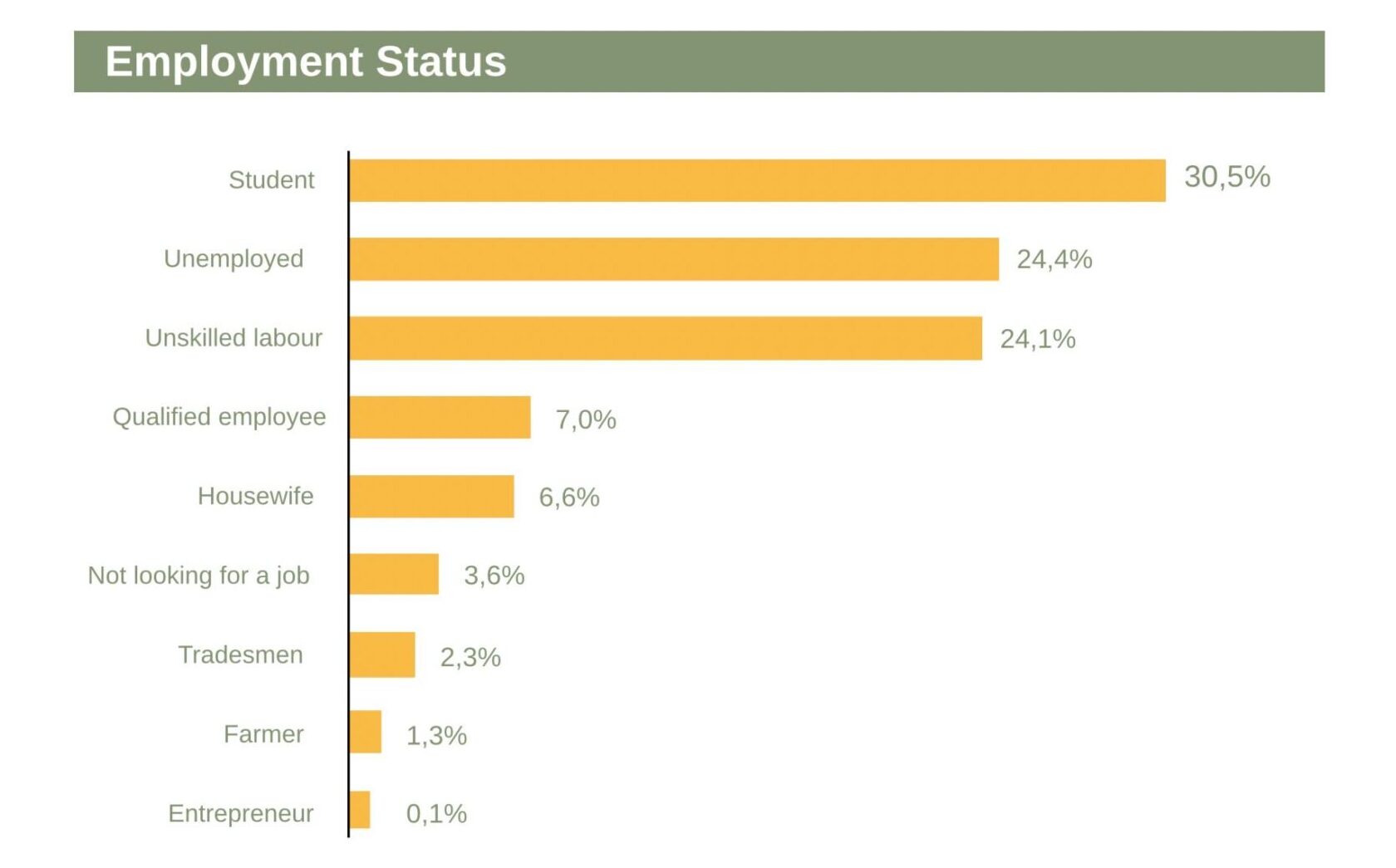

According to the research, approximately 34 percent of Kurdish youth are employed. However, 24 percent of this rate consists of unskilled workers. In other words, only 10 percent of Kurdish youth are employed in qualified jobs. The rest are either unskilled workers or unemployed. When these figures are compared with the national average in Türkiye, the disadvantaged situation of Kurdish youth becomes even more apparent.

While nearly one out of every two young people in Türkiye is employed, this rate is about one-third among Kurdish youth. When the gender distribution in employment is analyzed, it is seen that the disadvantaged position of women is even more entrenched among Kurdish youth.

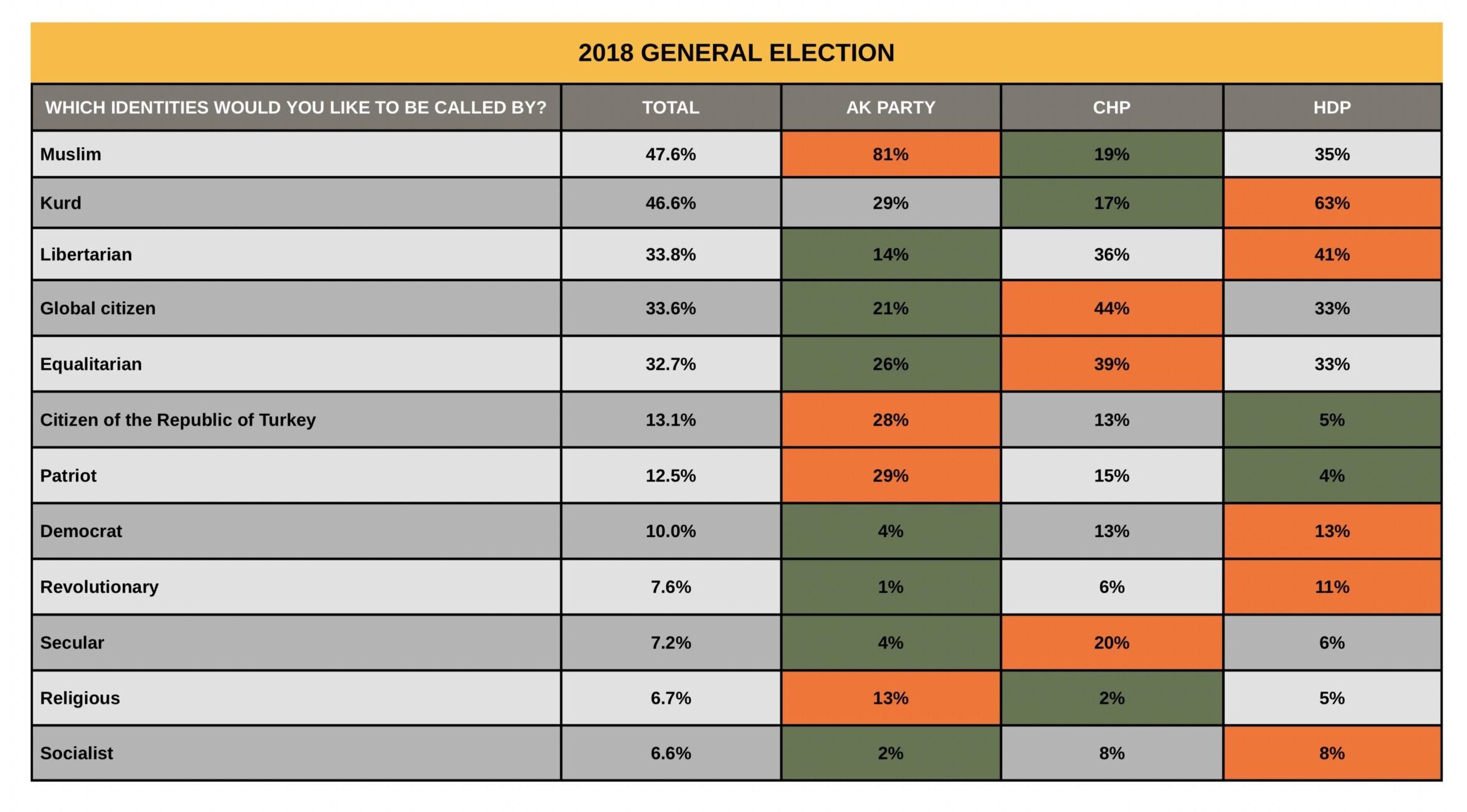

The research shows that Kurdish youth maintain their Kurdish identity and connect with universal identities. While young people broaden their primary identity toward universal identities, they also emphasize religious beliefs. The identities most emphasized by young people are Muslim, Kurdish, and libertarian. However, the relationship between political tendencies and identification is evident. While the emphasis on Muslim identity is significantly stronger among AK Party youth and the emphasis on Kurdish identity is less than half of that, the opposite is observed among HDP youth. A significant proportion of AK Party youth strongly identify as citizens of the Republic of Türkiye, whereas this proportion is markedly lower among HDP supporters.

One of the important findings of the research is that young people, especially those born in or long-term residents of the western provinces of Türkiye, identify themselves geographically and culturally as Turkish. A significant number of these young people hope to build their lives in Türkiye and continue to culturally identify as “People of Türkiye” despite their experiences. Although this situation is not a direct result of the HDP’s ‘Türkiyelileşme’ policy (policy of fostering a shared ‘People of Türkiye’ identity), the party’s policies and discourse seem to have contributed to helping young people reconcile with this position.

On issues such as gender and freedom of belief, Kurdish youth are more open-minded than those in the rest of Türkiye. While two-thirds state that women can go out at any time they wish, the view that Cemevis should be recognized as places of worship is supported by more than half of the youth. Young people living in the western regions adopt a more open stance compared to those living in their own Kurdish provinces. Again, women express significantly more positive opinions than men on issues directly related to their own lives, such as working, receiving education, and going out at any time they wish.

Tolerance for different identities remains weak among Kurdish youth, even though they are more open than the rest of Türkiye on issues such as gender and freedom of belief. The identities they want to distance themselves from the most are as follows: members of religious sects/devout individuals, homosexuals, atheists, Syrians, and Arabs.

On the other hand, as mentioned above, despite sharing a Turkish identity and culture, nearly half of Kurdish youth state that they would prefer not to have a Turkish partner. One of the main reasons for this response is the discrimination experienced by young people. Despite their intention and plans to live in Türkiye and build a future in the western provinces, the high proportion of those who do not want to have a Turkish partner is a striking finding, as it indicates that discrimination and its effects create barriers between the groups. This data suggests that Kurds, and particularly Kurdish youth, have a “Kurdish habitat” in the western provinces where they can live, and that having such a habitat may facilitate distancing from the wider society.

Cultural Structure

Kurdish youth resemble the rest of the young population in Türkiye in areas such as internet use, as they also use the internet intensively on a daily basis. In terms of usage rates among social media platforms, Twitter stands out prominently among Kurdish youth. While approximately 30% of other youth use Twitter, the rate reaches 44% among Kurdish youth. Kurdish youth view Twitter, which has a political nature, as an alternative information source to mainstream media. The fact that Kurdish political and social agendas are shared first-hand on this platform also attracts young people to Twitter.

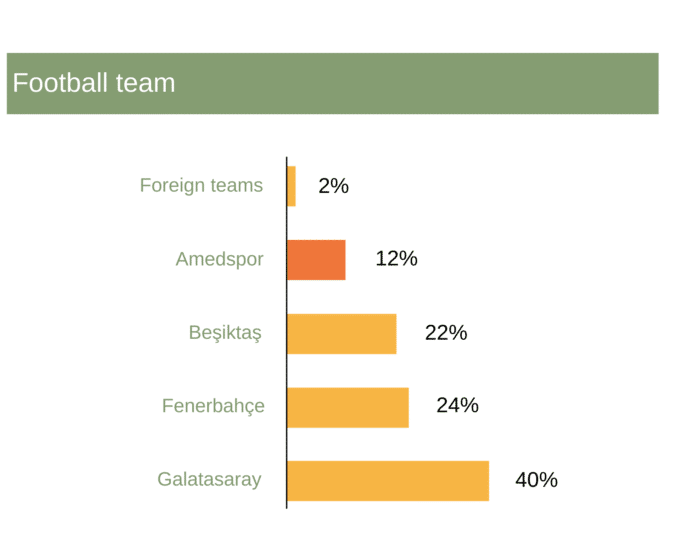

Kurdish youth reflect their uniqueness alongside similarities in areas such as music and football. Ahmet Kaya is the artist they listen to the most, while Sezen Aksu is the most popular female artist. In contrast to the general trend, young people like Kurdish artists such as Ciwan Haco, Şivan Perwer, Mem Ararat, Şakiro, and Aynur.

Although they share similar habits in watching comedy, action, and daily TV series, Kurdish youth also display differences in their television viewing habits. Young people keep their distance from TV series about tribal customs and clans, as well as patriotic dramas centered on the Kurdish issue.

Although Kurdish youth support Türkiye’s big three football clubs, Amedspor is regarded as one of the ‘big four’ by these young people. Amedspor attracts more supporters in cities where the Kurdish issue is more prominently on the agenda, as well as in metropolitan areas far from the region, such as Istanbul and Izmir.

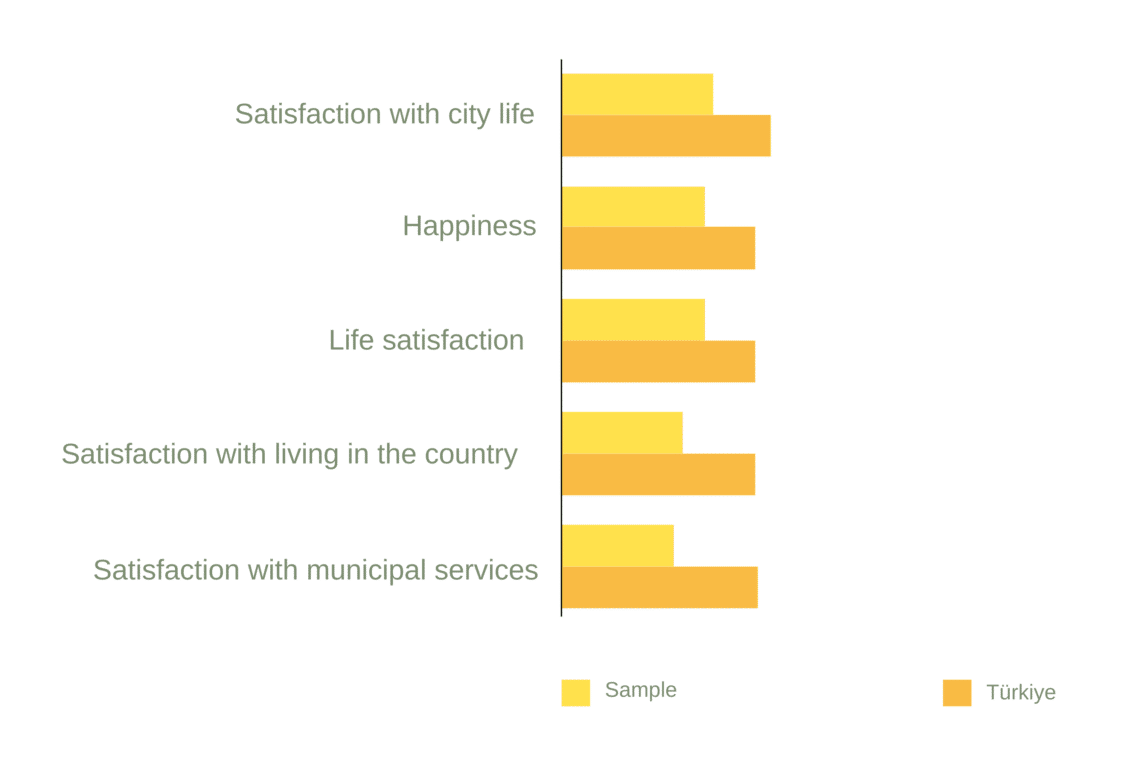

Apart from cultural differences, one of the most prominent characteristics distinguishing Kurdish youth from the rest of Türkiye’s youth is their significantly lower level of satisfaction. Although young people culturally identify as people of Türkiye, they are neither satisfied nor happy with living in the country. Given the political and social turmoil related to the Kurdish issue over the past five years, this situation may not be surprising. Nevertheless, the significant impact of the discrimination they face makes it one of the most pressing issues that demands careful consideration.

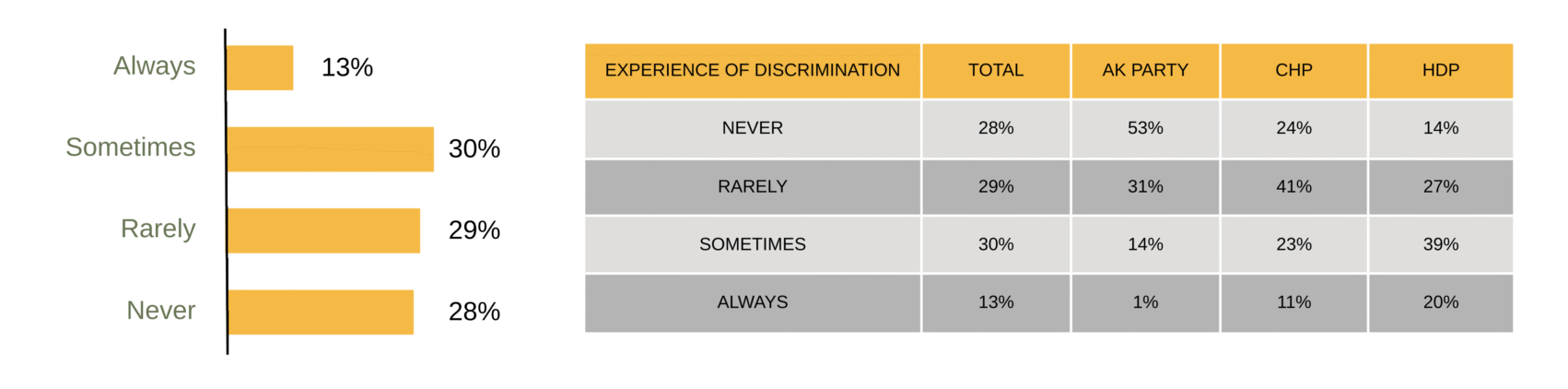

Discrimination

Nearly half of the Kurdish youth interviewed in the study reported having migration experience. 2 out of every 5 young respondents living in Türkiye’s Western provinces were born and raised in the West. Similarly, 1 out of 5 young respondents has been living in this city for more than 10 years. The overwhelming majority of young people report migrating for work or educational reasons. This high level of migration also increases the number of individuals who experience discrimination. 7 out of 10 young people report experiencing discrimination at varying levels.

The resolution process ongoing between 2013 and 2015 appears to have had a significant positive impact on the lives of Kurdish youth. In this period, while Kurdishness has turned into an identity that is no longer considered in a criminal context, the awareness of Kurdishness among young people seems to have increased. However, the transition from resolution to conflict has led young people to experience problems in their relationships with those around them. The increasingly visible and irreversible rise in Kurdish consciousness has begun to cause conflicts in interpersonal relationships. Young people report that discrimination increased during this period, and those subjected to discrimination appear to have been drawn to predominantly Kurdish settings as spaces for socialization.

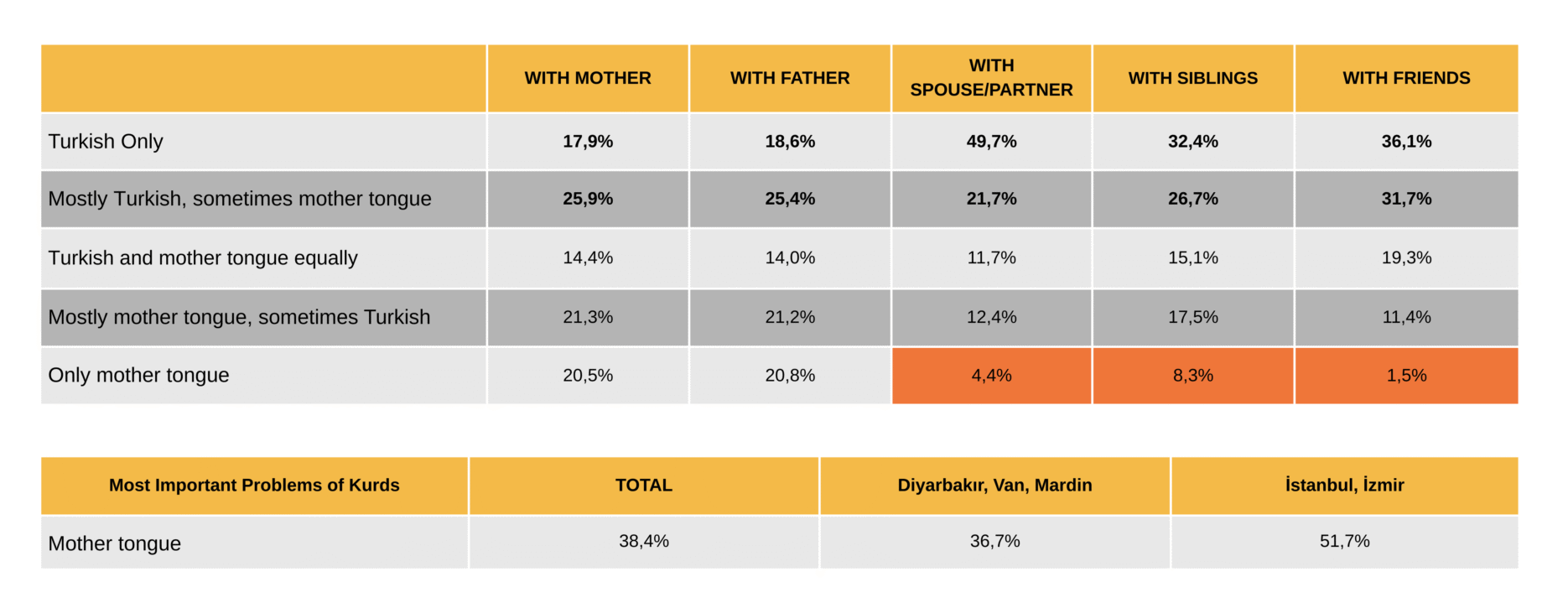

Mother Tongue

Although half of Kurdish youth report proficiency in their mother tongue, they rarely use it in daily life. At least one-fifth of respondents do not speak Kurdish and almost never use the language. Most of those who previously spoke Kurdish report that its use has declined over time and that the language has been forgotten. A significant proportion of those who report having an intermediate or good command of the language predominantly speak Turkish. Those who know Kurdish use it most frequently when speaking with their mothers and fathers. The proportion of those who speak mostly or exclusively Kurdish with their parents is approximately one-third. The vast majority of young people use Turkish when communicating with siblings, friends, and spouses/partners.

Young people who migrate to the West, influenced by the discrimination they face and the nationalist character of the political environment they encounter, turn to their mother tongue as a form of protection -both as a response to discrimination and as a safeguard against dominant nationalism. The consequences of losing their mother tongue are more apparent to them when they live in a non-Kurdish city. Combined with homesickness, the mother tongue becomes a more significant need and area of concern for those who migrated to the West later and experienced this encounter afterward, compared to those who were born and/or raised in the West.

The research findings indicate that while the use of Kurdish among young people is declining, there is a concurrent rise in Kurdish identity awareness and in demands for the collective rights of Kurds. Although this situation reflects an outcome contrary to the intentions of assimilation policies, Prof. Dr. Mesut Yeğen highlights the uncertainty surrounding whether the emerging identity of ‘Kurdishness without Kurdish’ will serve as a strong form of resistance if the trend continues, cautioning against complacency in assuming that ‘Kurdishness will persist even without the Kurdish language.’ The concerns of young people appear to align with this view. Almost all participants believe that Kurdish should serve as a language of instruction in schools, either independently or alongside Turkish.

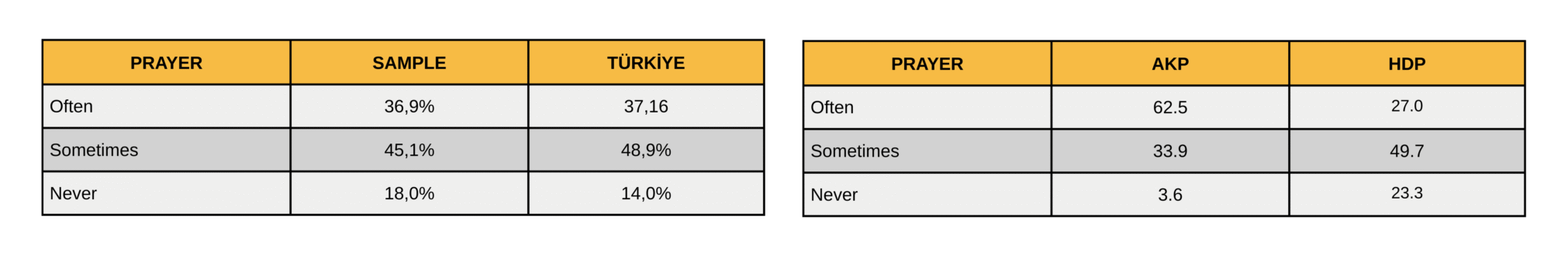

Religious Belief and Religiosity

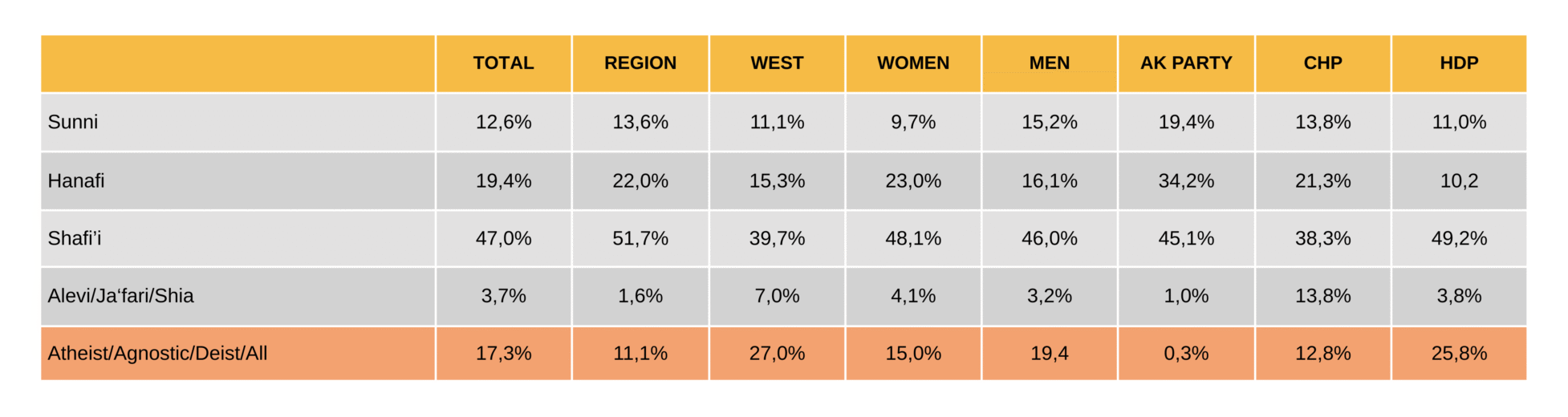

Kurdish youth, reporting a decline in their level of religiosity compared to five years ago, show similar patterns to the national average in Türkiye regarding religiosity and the practice of religious rituals. However, there is a correlation between religiosity and party affiliation. Nearly two-thirds of young AK Party voters and over one-quarter of young HDP voters report praying regularly.

Individuals living in Kurdish provinces tend to be more religious than those who have migrated to the West; married individuals are more religious than singles; those living with their families exhibit higher religiosity than those living with friends or alone; people from larger families show greater religiosity than those from smaller ones; those with longer village residency are more religious than those with shorter residency; and individuals with lower economic status and income demonstrate higher levels of religiosity compared to those with higher income. Said Nursî is by far the most prominent ‘religious opinion leader’ among young people.

One of the most striking findings under this heading is that the proportion of those who do not adhere to any religion is significantly higher among Kurdish youth compared to the national average in Türkiye. While this rate 10 percent or lower in nationwide youth surveys, 17.5 percent of Kurdish youth identify themselves as atheist, deist, agnostic, or similar.

While the proportion of Kurdish youth identifying as atheist, deist, or agnostic is quite low among those close to the AK Party, one quarter of Kurdish youth close to the CHP and HDP identify themselves this way. The higher propensity of young HDP supporters to distance themselves from religion compared to the overall context in Türkiye is noteworthy in the context of the relationship between political ideology and religious belief.

This finding partly confirms the general perception that young people close to Kurdish politics, as represented by the HDP, are distancing themselves from religion and becoming more secular. While secularization among Kurdish youth appears to be progressing more rapidly than among other youth, the acceleration of secularization across generations also appears to be linked to political attitudes.

However, among young people who vote for the HDP, the proportion of those with religious beliefs is approximately three times higher than that of those without. Again, among young people close to the HDP, the proportion of those who pray regularly is higher than that of those who do not pray at all. Nearly half of these young people report praying occasionally, albeit irregularly. Therefore, although the percentage of young people affiliated with the HDP who live without religion is higher than the average in Türkiye and secularization progresses faster among them, it should not be overlooked that the vast majority of these young people hold religious beliefs and are devout.

In addition to individualization and the influence of social environments among Kurdish youth, two additional factors reinforce the tendency to distance themselves from religion in relation to political attitudes. First, Kurdish youth perceive the AK Party as representing Islam on a national scale, and opposition to the AK Party contributes to their distancing from religion. Secondly, on a regional level, they recall the atmosphere in which ISIS and other Islamic armed groups in Syria attacked Kobani, and emphasize that these groups are currently mistreating Kurds in areas such as Afrin. These organizations’ claims to represent Islam accelerate young people’s alienation from religion.

Politics

The relationships of Kurdish youth with the AK Party and CHP are grounded in their own experiences rather than in historical narratives and stereotypes. Until recently, there was a widely held belief that the CHP carried an entrenched negative image among Kurds and that the AK Party was the second preferred party of HDP-supporting Kurds. However, today’s youth challenge this perception. For young HDP supporters, the AK Party’s alliance with the MHP and its shift from pursuing political solutions to the Kurdish issue toward reliance on military methods have contributed to Kurdish youth distancing themselves from the AK Party.

However, the HDP’s support for the CHP in western Türkiye during the March 31 elections, together with the CHP candidates’ careful language aimed at avoiding offense to Kurds and the opposition’s eventual victory, appears to have opened the door to political change in the country. Since the CHP, a key actor in this change, holds a traditional negative image among Kurds that is based on narratives rather than lived experience for young people, they critically examine the CHP they have personally encountered rather than the CHP portrayed in historical narratives, thereby granting it significant credibility. The rise of the CHP, supported by these factors, has positioned it as the second most preferred party among Kurdish youth.

As a result of this process, Ekrem İmamoğlu has gained significant popularity among Kurdish youth. Young people who think that Ekrem İmamoğlu has some similarities to Demirtaş also believe that the CHP should act more boldly in taking on the Kurdish issue.

Although young AK Party supporters generally act out of a sense of loyalty, one in five young people who voted for the AK Party in 2018 indicate that they will not support the party in future elections. During the period when the quantitative research was conducted, these young people were largely inclined towards boycott or undecided positions, while it appears that the newly established Deva and Gelecek parties, which had not yet been founded at that time, have partially succeeded in attracting their interest. Young people who are aware of these parties and have previously supported the AK Party view the Deva and Gelecek parties as a potential solution to their dissatisfaction with the AK Party.

In a potential presidential election, Selahattin Demirtaş is clearly the frontrunner among Kurdish youth, followed by Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and Ekrem İmamoğlu. However, in a scenario without Demirtaş, İmamoğlu is projected to receive more than twice as many votes as Erdoğan. This suggests that in a scenario where the opposition runs a single candidate with a profile like İmamoğlu, Kurdish youth would likely have no difficulty supporting the candidate.

Kurdish Issue, Resolution Process, and Deradicalization

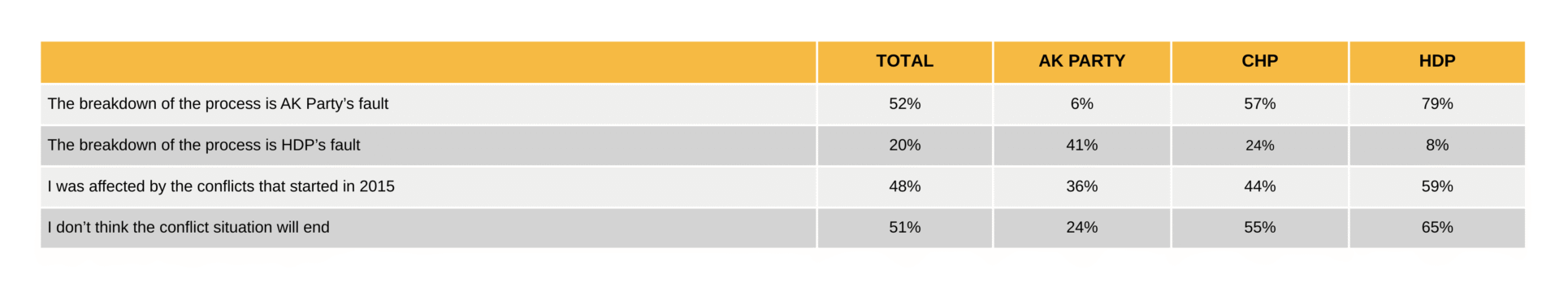

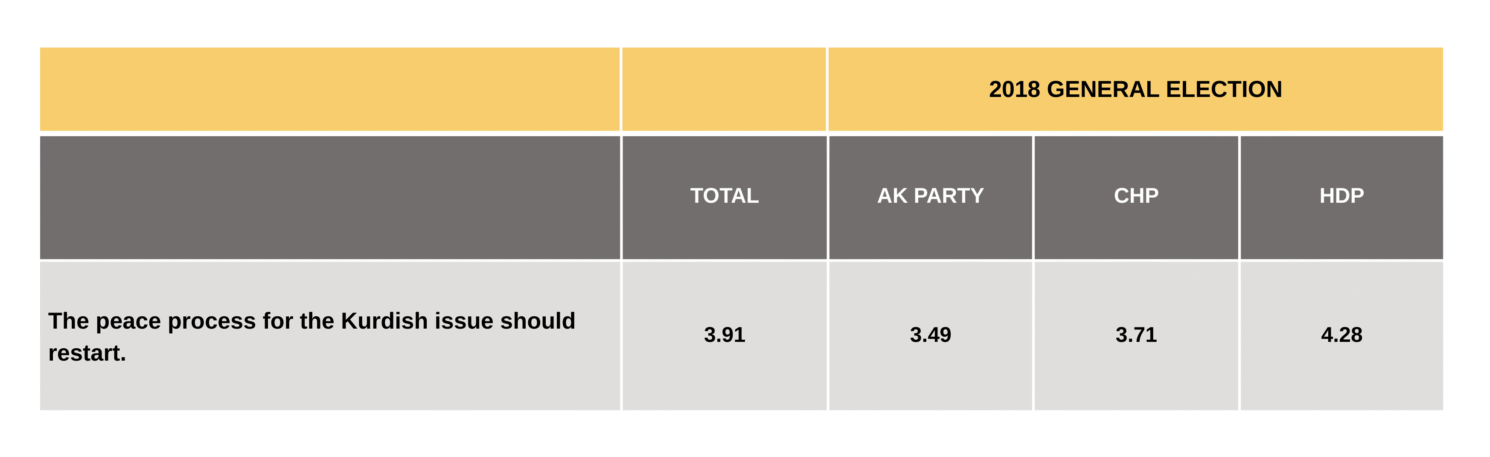

Young people report that discrimination decreased and life became easier during the periods when the Kurdish issue was undergoing a resolution process. Although the actors whom young people hold responsible for the breakdown of the resolution process vary according to party affiliation, and despite the current situation painting a pessimistic picture, the youth demonstrate a strong demand for the resolution of the Kurdish issue. Among those who report being more physically or psychologically affected by the period of violence, as well as among those who most strongly demand a new resolution process, the proportion of young people supporting the HDP is higher.

Turgut Uyar concludes his poem A Speech for Abdo from Malatya with the lines: “Since I came into this world / if I don’t die, if I don’t kill / who will notice me?” These lines carry a significant implication regarding violence as a means to gain attention and perhaps to attract interest.

During periods of heightened violence and increased attention, a clear tendency toward violent methods was observed among young people. However, both the consequences of the wave of violence that turned cities into battlefields and the military setbacks of the PKK in Türkiye and Islamic armed groups in Syria are prompting young people to reflect. Additionally, the decreased visibility of violence across Türkiye is reducing its appeal as a focal point.

On the other hand, the rise of Kurdish politics in the civilian sphere, particularly through the HDP, and the popularity of a figure like Demirtaş convey a message that the struggle can also expand within civil society. When all these factors are considered together, it appears that Kurdish youth today show a declining tendency toward radicalization and an increasing interest in civilian methods. This situation appears to be the case for both young people close to the HDP and those within the Islamic community. For example, young people close to the Hezbollah tradition prefer to be identified not with Hezbollah itself but with today’s Hüda-Par.

Summary

In an era marked by accelerating global dynamics, it is not only incorrect to evaluate Kurds through outdated frameworks, but it is also evident that Kurdish youth, being a more dynamic group, are more profoundly affected by change.

On the other hand, the research data reveal what is overlooked when Kurds are treated as a monolithic group. Kurdish youth demonstrate variability depending on their gender, whether they live in their hometowns or in the western regions, their level of religiosity (religious or secular), and their political affiliations, whether close to the HDP, the AK Party, or other political groups.

Considering this heterogeneous structure in assessments and policy-making regarding young people appears to be a key factor that will affect the effectiveness of communication established with them.

(Perspektif Online, November 3, 2023)